Last Saturday I drove to Wicklow, to the house our friends Suzy and Danny bought after the pandemic, when we had given up hope of all living in the same neighbourhood in Dublin. This weekend they will move again. The boxes were packed, ready to be shipped on a pallet down the Suez Canal to meet them in their new home in Australia.

At their going-away drinks, I watched them have the same conversations again and again about packing and logistics, about what they’ll miss most and what they won’t. “What’s hardest,” Suzy said, staring into one of the fishbowl gin and tonics we were drinking, “is that your friendships won’t grow from here. You might lose touch or remain close, but the most you can hope for is some long-range maintenance.”

When we say goodbye next week, it won’t be to close friends but to something more like family.

I met Suzy when we were both pregnant, and I liked her immediately – her intelligence, her dark humour, the steadiness she radiated in everything from the way she drove a car to how she made a cocktail. Our husbands quickly became friends too. Even our toddlers were inseparable. In March 2020, we planned a weekend away in the west of Ireland. When the first lockdown was announced the following day, we decided to stay put, unsure if our marriages or sanity would survive indefinite lockdown in our tiny flats. What was meant to be a few days turned into six months.

READ MORE

We cooked and cleaned together, worked in shifts, and tried to keep two small children entertained while the world shut down. It was messy and intense, an experiment in communal living – like being married to three people instead of one – and we were close in different ways, P and Suzy competing over the crossword on a Sunday and Danny and I having long emotionally earnest conversations while peeling potatoes or shepherding children halfway up a mountain.

There were arguments about chores and parenting styles, about whose turn it was to cook or go for a walk to escape the chaos. But there was also a rare kind of ease. The children, the same age, moved like twins through those months, wild and inseparable, bickering like siblings. Even now, years later, they still have that bond.

By the end of the summer we returned to our nuclear units, but something fundamental had changed. Living together had dissolved the normal boundaries of friendship; we’d seen each other at our most unguarded and tired, and if we didn’t like everything we still felt connected for life.

When Ted was diagnosed with leukaemia, Suzy, Danny and their girls were among the first people I could see. They were the friends I never had to perform normality with – the “everything’s fine” act designed to put others at ease but which leaves you utterly drained. When I finally visited their new house, Suzy held her baby Sonny and listened as I tried to speak. Her face crumpled in a mirror of my own grief – but somehow I knew it wasn’t because she was sorry for me or had a child Ted’s age, but because we were family and she loved him fiercely too. That kind of friendship feels impossible to remake at 41.

I can blame a traumatic event for narrowing my social world, but in truth, the pandemic contracted all of our friendships. And friendships in midlife shrink for everyone. There are the obvious reasons – children, work, fatigue – but there’s also something subtler: a collective retreat from effort. I sometimes wonder if part of what we call friendship fatigue is really exhaustion with the work real closeness takes.

Online, we curate manageable slices of connection; in real life, we forget that friction is often how intimacy grows.

Lately I’ve seen a spate of articles on “friendship break-ups”, that advise the reader to let go of the bonds that no longer serve them. There’s something to be said for calling time on friendships that no longer nourish us, but maybe we’re too quick to mistake the normal friction necessary for growth for something not worth bothering with. Real friendship, like any long relationship, needs a tolerance for discomfort.

My mother, by contrast, still meets her friends – “her girls” – at least once a week. I know that’s down to her kindness and tenacity, but I also suspect she hasn’t lost quite so many of them to the cost of rent.

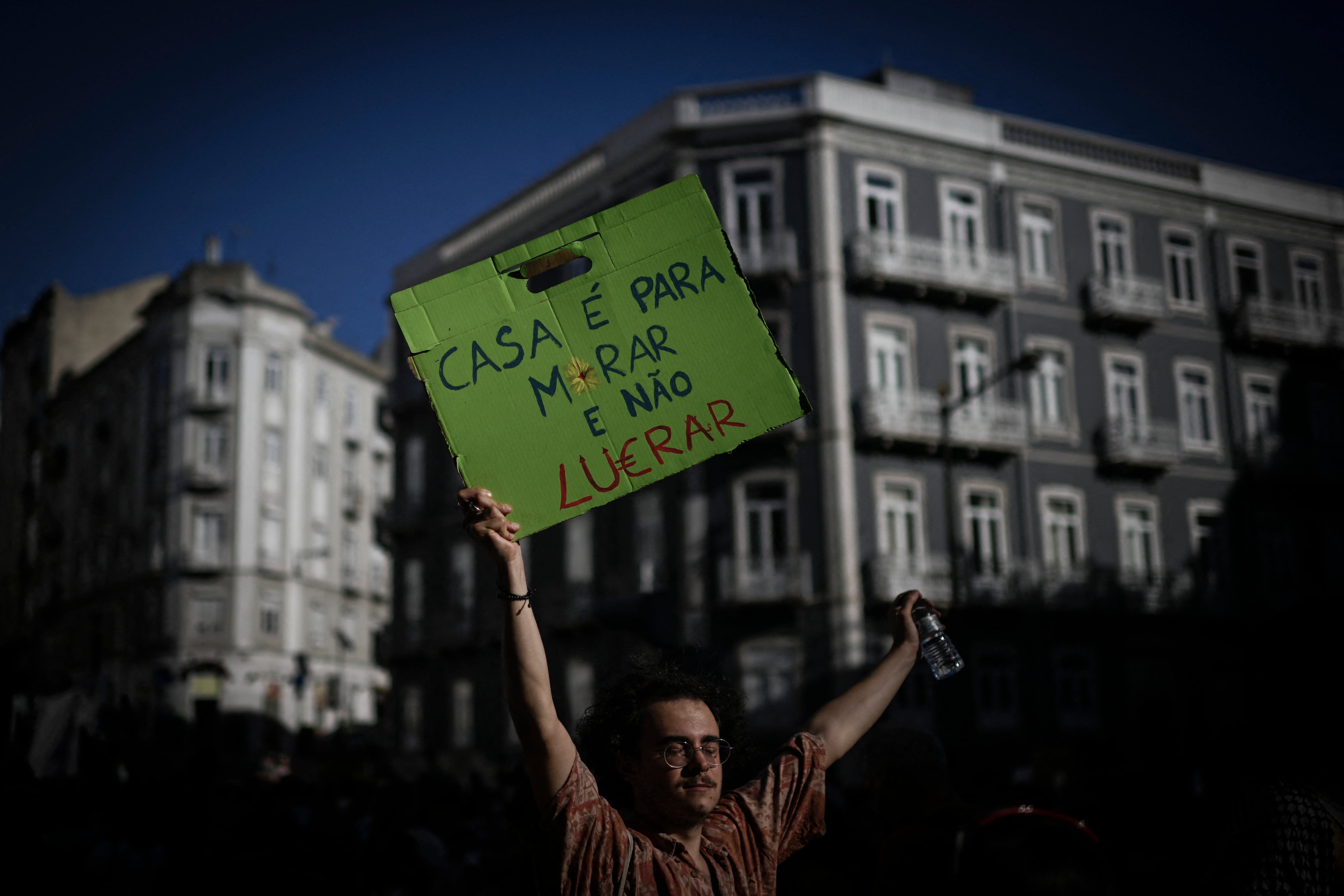

All through my adult life, close bonds have been disrupted by emigration – siblings moving to the States for work, friends to London, young parents leaving Dublin in search of affordable housing, and now to Australia, which, as Suzy put it, in geographical terms is the same as moving to space.

Ireland has always been a country that can’t seem to hold on to its own, shrugging its shoulders at the mass exodus of the young, as though this were a state as natural as the weather. But in recent years emigration has changed shape.

It’s no longer just a rite of passage for people in their 20s; more and more, it’s a midlife decision – couples in their 30s and 40s, already raising children, who have built lives here but can’t sustain them. Less adventure, more surrender.

[ As Ireland has become richer, more Irish people are heading to AustraliaOpens in new window ]

The latest CSO figures show that almost half of those emigrating from Ireland are now aged between 25 and 44. Australia is a choice destination, with more than 10,000 Irish moving there last year alone.

I’ll miss my friends. But what I’ll miss most is the chance to keep building the friendship we already had.

And I’m sad they’re going, but I’m sadder still that the country I love can’t hold on to the people I love.

- Are you Irish and living in another country? Would you like to share your experience with Irish Times Abroad, something interesting about your life or your perspective as an emigrant? You can use the form above, or email abroad@irishtimes.com with a little information about you and what you do. Thank you