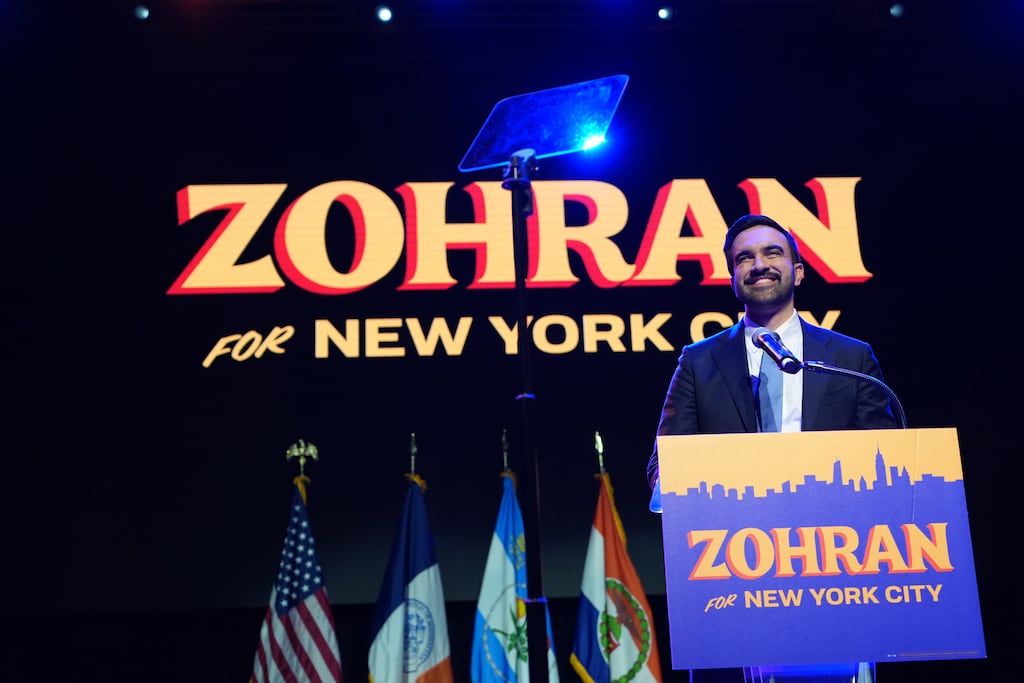

As the extent of Zohran Mamdani’s stunning victory in the New York mayoral race became apparent on Tuesday night, it was hard to ignore the similarities with Catherine Connolly’s successful presidential campaign in Ireland.

Until late last year, Mamdani was an obscure state senator. He had support levels of about 1 per cent when he announced his intention to seek the Democratic nomination for the mayoral election. To add to the Sisyphean task he set for himself, he was born in Uganda and, as well as being the child of immigrants, is a Muslim and self-described socialist. .

Unsurprisingly, his political enemies – from Donald Trump to Fox News’s Sean Hannity to the New York tabloids – were quick to brand him a “commie”.

Connolly had better comparative recognition, but she was hardly a household name. An Independent TD who was part of a left-wing alliance, she was a relatively marginal presence in Irish politics.

READ MORE

How did two candidates on either side of the Atlantic succeed in disrupting so effectively? Primarily, it was by building broad coalitions of voters who were disaffected by the status quo. That manifested as ground-up movements rather than the top-down-style campaign that has been the norm for a generation. A standout feature of both was that they mobilised substantial armies of enthusiastic volunteers who bought into their central themes, vision and “authenticity”.

[ After fairytale in New York, mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani starts a new chapterOpens in new window ]

In general, both framed themselves as anti-elite, anti-establishment and progressive. Both made the genocide in Gaza central components of their campaigns.

That said, Mamdani’s core argument was that New York was becoming a haven for the wealthiest, with middle-income and low-income families struggling badly because of big hikes in the cost of living. He set out a small number of very clear proposals that had resonance with voters who believed the Big Apple had become unaffordable. He wanted to impose new taxes on the wealthiest citizens. He also proposed free bus travel, a rent freeze in the one million apartments that were rent-stabilised, cheaper universal childcare and – most controversially – setting up state-run grocery stores that would be in a position to sell food at lower prices.

Ground-up campaigns are hardly new. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 in England was caused by high taxes from the Hundred Years War, the impact of the Black Death and increased agitation from serfs to end the feudal system which bound them to the estate of their lords.

What Mamdani’s team did differently was to assemble a huge ground operation of volunteers. Teams of canvassers, mostly young, swarmed into every community across the five boroughs of New York to spread the message. Mamdani made no bones of the fact it was a populist campaign – the rent freeze in particular struck a chord with voters. By the time New Yorkers went to the polls, the campaign team had attracted an astonishing 100,000 volunteers, and an operation financed by thousands of small donations. An adept media performer, Mamdani posted quirky and polished videos, with high production values, on TikTok and Instagram. They showed him meeting taxi drivers, visiting Hispanic communities, going in and out of local stores, running the New York marathon.

The combination of all those factors had an electrifying effect. People came out in droves to vote. Mamdani was the first candidate since 1969 to win more than one million votes in a mayoral election in New York.

In Ireland, Connolly’s campaign team also sought organic reach, albeit on a smaller scale. Their campaign – using a brand identity that was inspired by traditional Galway shopfronts, but coincidentally bore a striking resemblance to Mamdani’s – was modelled on the templates from the abortion referendum in 2018 and the same-sex marriage referendum in 2015. They recruited large numbers of volunteers to knock every door possible and, at the same time, have the widest possible reach on social media.

An impressive 15,000 people volunteered to work on Connolly’s team.

The main opponents of both candidates cleaved to more traditional electioneering methods and media and, ironically, lost out on them as well. Two billionaires, former mayor of New York Michael Bloomberg and hedge fund manager Bill Ackman, pumped millions into the campaign of Andrew Cuomo, who stood as an Independent. It had no impact on Mamdani’s inexorable rise.

An interesting corollary is the changing disposition of the electorate. It is probably more apparent in the US, UK and continental Europe than in the Republic, although the relatively high number of spoiled votes in the October election suggests a trend in that direction.

Mamdani scored highly among Latino voters in the election. Many of those would have been former Biden and Obama voters. Some 48 per cent of all Latino voters plumped for Trump in 2024. This time around, in New York, they returned to the Democrats. In England, Labour’s “red wall” across the north of the country delivered scores of seats for the party over a century. It lost them to the Tories in 2019, recaptured them in 2024 – but the party is now in real peril of losing them to Nigel Farage’s anti-immigrant Reform Party.

In northern France, former communist strongholds have fallen to Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally in recent elections. The same has happened in Spain where, in working-class Madrid, for example, some former supporters of the populist left-wing Podemos movement now support the right-wing populist movement Vox.

There is a lot of volatility and churn in politics right now as voters swing from left to right.

Both Mamdani and Connolly claimed their victories signalled the birth of “new movements”. Time will tell if that is the case, or if their wins merely reflect a wider trend of electoral volatility. The left everywhere will be taking note.