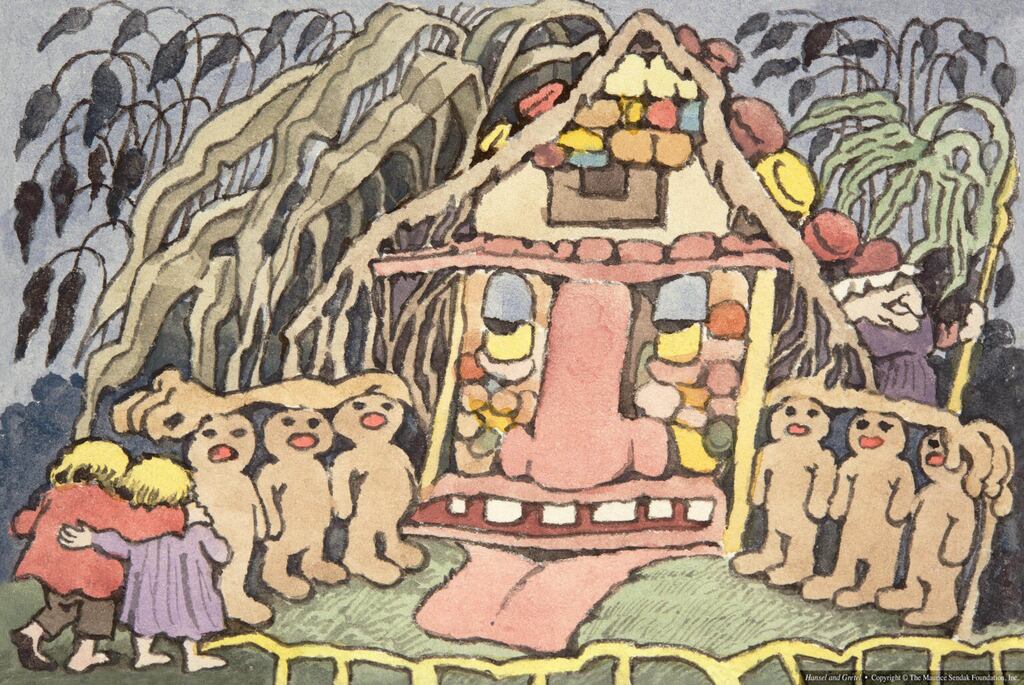

The spookiest of seasons has arrived, and with it the first children’s title from High King of Horror writing, Stephen King. In Hansel and Gretel (Hachette, 6+, £20), King has written a new version of the grim Grimm fairytale, to complement designs that the late great American illustrator, Maurice Sendak, created for Engelbert Humperdinck’s operatic version of the story.

It is hard to know which is creepier, Sendak’s chilling crayon picture of a sack of crying children or King’s succinct image of “a witch on a broomstick, flying through the clouds with a bag behind her filled with screaming kids”. There is, as per convention, a hard-won happy ending, where Hansel and his sister are rewarded for their courage by reunion with their father, but if your young reader likes fairytales with a gleefully Gothic edge, this is the version of them.

The bestselling Young Adult fantasy writer Leigh Bardugo makes her picturebook debut this month too, with The Invisible Parade (Hachette, 6+, £16.99), a collaboration with John Picacio, which brings life to the rituals of the Day of the Dead. Cala is mourning her grandfather, when a family trip to his grave brings her face to face with four shadowy horsemen, who have much to teach her about mortality. Picacio’s illustrations add richness to the liminal setting, where it is “hard to say who might be the living and who might be the dead”. While the Dia de los Muertos context makes The Invisible Parade a perfect title for Halloween, the themes of grief that it explores are timeless.

In Mikey Please’s The Cave Downwind of the Cafe (HarperCollins, 3+, £14.99), a traditional fairytale monster gets a reinvention. Glumfoot the goblin may have grown up in a cave eating “bogey broth served with a spade”, but he dreams of something sweeter, a fresh pastry treat, perhaps, from the cafe downwind of his cave. When he meets an ogre who plans on eating its owner, Glumfoot must intervene, by serving up a spectacularly disgusting platter to cater to the ogre’s taste. The real pleasure of Please’s colourfully illustrated book is the rhyming scheme, which offers gobfuls of internal echoes and unexpected juxtapositions, while whetting the appetite for the invention of gross afterschool snacks.

READ MORE

The Scottish bard Robert Burns’s most famous poem, Tam O’Shanter, gets a child-friendly workaround in Simon Lamb’s Mat O’Shanter: A Cautionary Tale (Scallywag Press, 5+, £12.99). The hero here is “a churlish adolescent/whose narrative is quite unpleasant”. Refusing to go home before the “wizard hour”, Mat is faced with the consequences of his behaviour when he is confronted by various mythological monsters, given expressive life by Ross McCrea’s pencil sketches. Although inspired by Burns’s original lyric, there is a Dahlian rhythm to both the rollicking rhyming scheme and the grotesquerie of the scenario, in which Lamb refuses to let the ghastly Mat get away with bad behaviour.

Perhaps Mat should have taken a lesson from Martha, the Megalosaurus who is the star of Olivia Hope’s The Lonely Only Dinosaur (Gill Books, 2+, 16.99), which is illustrated by Anna Süßbauer in bold bright colours. Martha lives alone in a swamp, where all the other living creatures seem to have companions. When she spots a little dinosaur across the pond, she gives her “friendliest, roariest roar”, but she accidentally scares him away. Martha must learn to be gentle if she wants a new friend. There is proper danger as Martha battles with her instincts in her quest for friendship, but the lessons around co-operation and kindness sing clearly in the picture book’s happy ever after.

In Sarah Crossan’s debut picture book A Totally Big Umbrella (Walker, 3+, £12.99), a collaboration with illustrator Rebecca Cobb, Tallulah has to figure out a way to regulate her feelings too: in this case the anxiety that overwhelms her every time it rains. Rain is “sneaky” and ruins everything, Tallulah believes, so she arms herself with an umbrella, then two. She even builds an umbrella cave, to make sure she doesn’t get “totally washed away”, before realising that there is actually fun to be had in a spontaneous soaking: the important thing is having friends and family with whom to share your worries, and your joy.

Tina Oziewicz and Aleksandra Zajac offer an alternative mode of coping with difficult feelings: checking up on them in the evening hours, when a feeling’s true nature is revealed. What Feelings Do at Night (Pushkin Children’s, 3+, £14.99), translated by Antonia Lloyd Jones, is a charming catalogue of emotions that puts both bad and good feelings in their place, illustrated by rounded friendly monsterly creatures in shaded charcoal sketches that are easy on the tired eye. So what do feelings do at night? Well, Rebellion is out dancing. Patience is washing herself thoroughly and combing her hair. Curiosity is restless: “she has so many more interesting things to do”. And Common Sense? Well Common Sense is, of course, very tired: he crawls under his quilt and accepts the inevitable: sleep.